Established 2005 Registered Charity No. 1110656

Scottish Charity Register No. SC043760

DONATE

RECENT TWEETS

The figures tell a sobering story. In the last five years, homelessness has increased by 40 per cent in the UK. What’s more, a staggering 80 per cent of the UK’s homeless population report mental health problems. But will they get the help they need?

My experiences as a community psychiatric nurse suggest not all will.

After all, how could they? Funding for mental health has been cut for three consecutive years now.

Since last year, there’s been an eight per cent fall in mental health budgets and a rise in referrals of 20 per cent to Community Mental Health Teams (CMHTs). No wonder so many healthcare professionals are feeling the pressure of having to do a lot more with less.

Across the board, cuts are being made to the number of mental health professionals based within homeless organisations. Previously, a hostel might have had a mental health professional on site, or specialist groups to advise. Now there are now just the basics: a bed and a roof over your head.

In my job, I rely on homeless voluntary organisations that run throughout winter to meet some of the shortfall. But now, as summer approaches, they are not there.

The result is many people suffering an episode of full mental health – whether they are experiencing a psychotic episode or feeling suicidal – are presenting to A&E and often end up being discharged back to the streets.

Some 35 per cent of homeless people were admitted to A&E complaining of a mental health problem over the past six months.

The current psychiatric hospital bed crisis makes accessing hospital care difficult. So what are you to do?

There is hope. The homeless Hospital Discharge Network helps homeless people in London who require ongoing nursing support following discharge from hospital and offers ‘step up, step down’ care. This is the equivalent to what the non-homeless get after a hospital visit, for example a nurse to visit them in their home.

The different they make is immeasurable, and we need more money invested in these services if we are to meet the demands and to prevent worsening of mental health rates in the homeless population. The problem of cuts in other essential areas has an impact too.

As a psychiatric nurse, I should spend my time supporting, educating and treating mental health and general wellbeing. Instead, I spend my days filling out applications for welfare support or contacting the local council to help find emergency accommodation for our service users. Who else, my patients ask, is there to ask for help?

According to the Mental Health Policy Group, by 2030 we will be witnessing two million more people in the country with mental health needs. It is essential that proportions of the budget are specifically set aside for homeless people.

This is not just about being humane. To put it bluntly, the research shows time and time again, that it’s cheaper to address someone’s mental health issues when they first show up in a hostel than to wait until their situation becomes ever more complex. More collaborative working between services needs to be supported and emphasised, and a broader understanding of the cycle of factors contributing to poor mental health, including environment, substance misuse, physical health and social needs, is urgently needed.

We need to pull together as a nation to treat our most vulnerable as a matter of priority.

What do you think? Have you struggled to access mental health services? Tell us what you think: karin@thepavement.org.uk

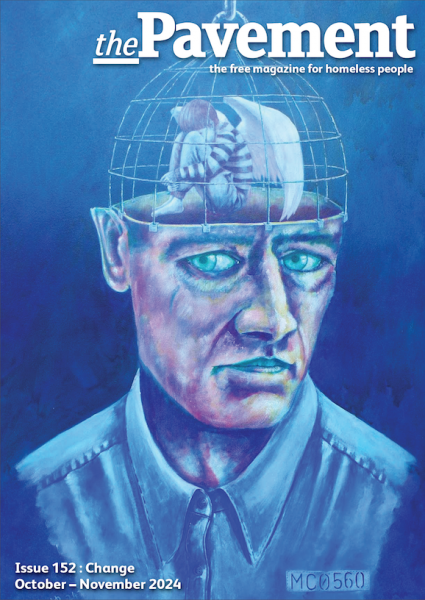

October – November 2024 : Change

CONTENTS

BACK ISSUES

- Issue 152 : October – November 2024 : Change

- Issue 151 : August – September 2024 : Being Heard

- Issue 150 : June – July 2024 : Reflections

- Issue 149 : April – May 2024 : Compassion

- Issue 148 : February – March 2024 : The little things

- Issue 147 : December 2023 – January 2024 : Next steps

- Issue 146 : October 2023 – November 2023 : Kind acts

- Issue 145 : August 2023 – September 2023 : Mental health

- Issue 144 : June 2023 – July 2023 : Community

- Issue 143 : April 2023 - May 2023 : Hope springs

- Issue 142 : February 2023 - March 2023 : New Beginnings

- Issue 141 : December 2022 - January 2023 : Winter Homeless

- Issue 140 : October - November 2022 : Resolve

- Issue 139 : August - September 2022 : Creativity

- Issue 138 : June - July 2022 : Practical advice

- Issue 137 : April - May 2022 : Connection

- Issue 136 : February - March 2022 : RESPECT

- Issue 135 : Dec 2021 - Jan 2022 : OPPORTUNITY

- Issue 134 : September-October 2021 : Losses and gains

- Issue 133 : July-August 2021 : Know Your Rights

- Issue 132 : May-June 2021 : Access to Healthcare

- Issue 131 : Mar-Apr 2021 : SOLUTIONS

- Issue 130 : Jan-Feb 2021 : CHANGE

- Issue 129 : Nov-Dec 2020 : UNBELIEVABLE

- Issue 128 : Sep-Oct 2020 : COPING

- Issue 127 : Jul-Aug 2020 : HOPE

- Issue 126 : Health & Wellbeing in a Crisis

- Issue 125 : Mar-Apr 2020 : MOVING ON

- Issue 124 : Jan-Feb 2020 : STREET FOOD

- Issue 123 : Nov-Dec 2019 : HOSTELS

- Issue 122 : Sep 2019 : DEATH ON THE STREETS

- Issue 121 : July-Aug 2019 : INVISIBLE YOUTH

- Issue 120 : May-June 2019 : RECOVERY

- Issue 119 : Mar-Apr 2019 : WELLBEING

- Issue 118 : Jan-Feb 2019 : WORKING HOMELESS

- Issue 117 : Nov-Dec 2018 : HER STORY

- Issue 116 : Sept-Oct 2018 : TOILET TALK

- Issue 115 : July-Aug 2018 : HIDDEN HOMELESS

- Issue 114 : May-Jun 2018 : REBUILD YOUR LIFE

- Issue 113 : Mar–Apr 2018 : REMEMBRANCE

- Issue 112 : Jan-Feb 2018

- Issue 111 : Nov-Dec 2017

- Issue 110 : Sept-Oct 2017

- Issue 109 : July-Aug 2017

- Issue 108 : Apr-May 2017

- Issue 107 : Feb-Mar 2017

- Issue 106 : Dec 2016 - Jan 2017

- Issue 105 : Oct-Nov 2016

- Issue 104 : Aug-Sept 2016

- Issue 103 : May-June 2016

- Issue 102 : Mar-Apr 2016

- Issue 101 : Jan-Feb 2016

- Issue 100 : Nov-Dec 2015

- Issue 99 : Sept-Oct 2015

- Issue 98 : July-Aug 2015

- Issue 97 : May-Jun 2015

- Issue 96 : April 2015 [Mini Issue]

- Issue 95 : March 2015

- Issue 94 : February 2015

- Issue 93 : December 2014

- Issue 92 : November 2014

- Issue 91 : October 2014

- Issue 90 : September 2014

- Issue 89 : July 2014

- Issue 88 : June 2014

- Issue 87 : May 2014

- Issue 86 : April 2014

- Issue 85 : March 2014

- Issue 84 : February 2014

- Issue 83 : December 2013

- Issue 82 : November 2013

- Issue 81 : October 2013

- Issue 80 : September 2013

- Issue 79 : June 2013

- Issue 78 : 78

- Issue 77 : 77

- Issue 76 : 76

- Issue 75 : 75

- Issue 74 : 74

- Issue 73 : 73

- Issue 72 : 72

- Issue 71 : 71

- Issue 70 : 70

- Issue 69 : 69

- Issue 68 : 68

- Issue 67 : 67

- Issue 66 : 66

- Issue 65 : 65

- Issue 64 : 64

- Issue 63 : 63

- Issue 62 : 62

- Issue 61 : 61

- Issue 60 : 60

- Issue 59 : 59

- Issue 58 : 58

- Issue 57 : 57

- Issue 56 : 56

- Issue 56 : 56

- Issue 55 : 55

- Issue 54 : 54

- Issue 53 : 53

- Issue 52 : 52

- Issue 51 : 51

- Issue 50 : 50

- Issue 49 : 49

- Issue 48 : 48

- Issue 47 : 47

- Issue 46 : 46

- Issue 45 : 45

- Issue 44 : 44

- Issue 43 : 43

- Issue 42 : 42

- Issue 5 : 05

- Issue 4 : 04

- Issue 2 : 02

- Issue 1 : 01

- Issue 41 : 41

- Issue 40 : 40

- Issue 39 : 39

- Issue 38 : 38

- Issue 37 : 37

- Issue 36 : 36

- Issue 35 : 35

- Issue 34 : 34

- Issue 33 : 33

- Issue 10 : 10

- Issue 9 : 09

- Issue 6 : 06

- Issue 3 : 03

- Issue 32 : 32

- Issue 31 : 31

- Issue 30 : 30

- Issue 29 : 29

- Issue 11 : 11

- Issue 12 : 12

- Issue 13 : 13

- Issue 14 : 14

- Issue 15 : 15

- Issue 16 : 16

- Issue 17 : 17

- Issue 18 : 18

- Issue 19 : 19

- Issue 20 : 20

- Issue 21 : 21

- Issue 22 : 22

- Issue 23 : 23

- Issue 24 : 24

- Issue 25 : 25

- Issue 8 : 08

- Issue 7 : 07

- Issue 26 : 26

- Issue 27 : 27

- Issue 28 : 28

- Issue 1 : 01